Nissan’s place-based design process

Megan Neese is a senior manager in the Future Lab at Nissan Motor Ltd., a cross-functional team tasked with uncovering new business opportunities for the future of automotive.

In an article for EPIC, she explains how product companies are undergoing an identity crisis, as products become smarter, their nature changes, and even the definition of the industry that they service blurs.

This new system of systems brings with it a series of fundamental questions: What industry are we in? Who are our customers? What are our core competencies? A seemingly straightforward product development process of making decisions in a tidy cascade is of the antithesis this complicated mash-up of products, services, and systems where a change in one system can affect the usability and functionality of products and services in seemingly unrelated systems.

In this world, what is a product? Is the product the physical object and all of the associated data that it gathers, or is it the service that this information enables?”

This has big implications for Nissan”:

As a car company, we have found that new pressures on the industry and shifting expectations for smarter, connected products have very much changed the scope of our market. Our definition of “customer†might no longer be restricted to individual owners, but includes a series of stakeholders from city planners to service providers. How we study and plan for this future has evolved, if our products will be connected we must understand what systems these products are connecting to.

Urban design in particular has emerged “as the most significant determinant of the travel patterns in cities around the world” and the “automotive industry has come to rely on urban planning to value and prioritize the role of the car in cities”.

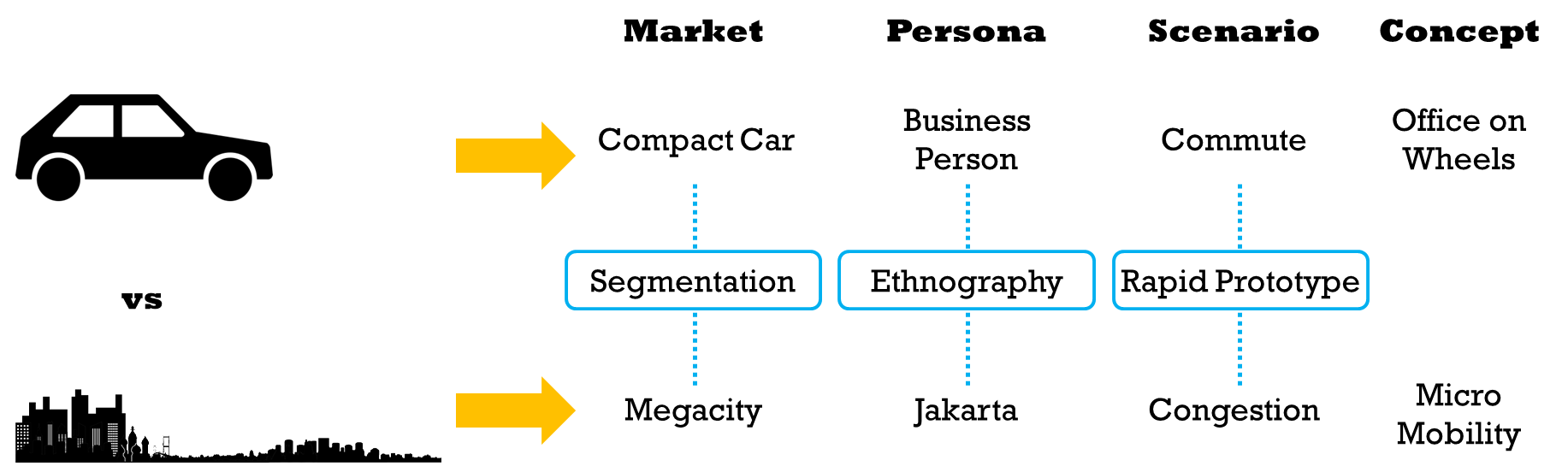

This now means that the design innovation process has changed: from market segmentation-based research to place-based ethnographic research:

Traditionally, if we were planning a new product we would start with market segmentation based on an interesting demographic cohort or emerging mindset. This would allow us to identify a target customer group, such as “business people,†whom we could then study ethnographically to uncover opportunities that we could address with a new product. For example, commuting is a relatively complicated driving scenario often fraught with functional and emotional needs. By understanding the complexity of a daily commuting situation we could have a clear problem for which to solve using the design process.

But then, as we began to consider our problem space in the broader context of the future of the city we realized that this research and design process needed to change. Now that we are starting with a place, our segmentation is based on cities rather than mindset groups or product categories, our ethnography is based on that place (e.g. Jakarta) rather than a persona, and concepts are developed from a systems view rather than a problem space.