From New Yorker staff writer Kyle Chayka comes a timely history and investigation of a world ruled by algorithms, which determine the shape of culture itself.

Today, it is of utmost relevance to study people’s attitudes, motives, and behaviours in relation to the fact that we live in a culture of surveillance. This includes the need for cultural and ethical perspectives to understand and nuance contemporary discussions on surveillance, not least in the highly digitalised context of the Nordic countries.

“The challenge is that a consumer doesn’t see the true value that manufacturers see in terms of how that data can help them in the long run. So they don’t really care for spending time to just connect it.”

"What’s mine is mine: unpicking the psychological reasons people like to own things" is the title of a highly recommended article by Claire Murphy of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Paying individual people for their health data will widen inequalities and reduce altruism, luring people to sell their privacy. Health data should instead be treated as collective property, and commercial profits should be shared with the public.

“There is nothing shocking or radical about ending an economic practice that has too many negative externalities. We have banned certain kinds of economic activity in the past because of them being too toxic for society. ”

A report by researchers at New York University warns that biometric and other digital ID systems that are increasingly linked to large-scale human rights violations, especially in the Global South.

It’s easy to assume that because some data is “personal”, protecting it is a private matter. But privacy is both a personal and a collective affair, because data is rarely used on an individual basis, writes Carissa Véliz in the New Statesman.

With 'obfuscation' or 'data poisoning,' they are redoubling their efforts to prevent companies from tracking them online, writes Aurélien Defer in Le Monde. But these time-consuming and sometimes very complex methods of resistance have not become widespread.

Provides a foundational understanding of technical and social aspects related to online privacy

Covers modern application areas as well as underexplored issues (e.g., privacy accessibility, cross-cultural privacy)

Includes a dedicated part on forward-looking approaches to privacy that move beyond one-size-fits-all solutions.

With this product, writes anthropologist Sally Applin in MIT's Technology Review, "Facebook is claiming the face as real estate for its own technology."

People care and act to manage their privacy, but face steep psychological and economic hurdles that make not just desired, but also desirable privacy nearly unattainable. Approaches to privacy management that rely purely on market forces and consumer responsibilization have failed.

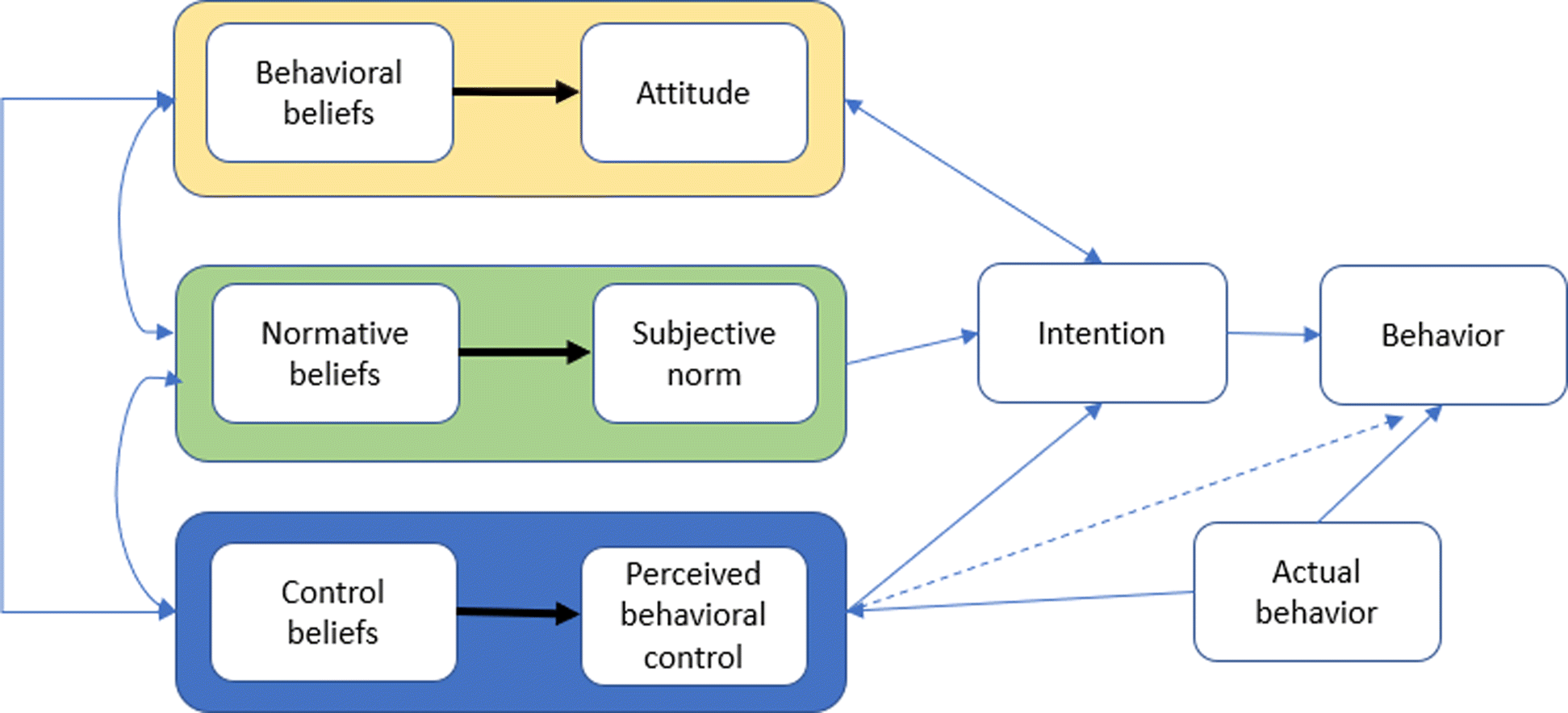

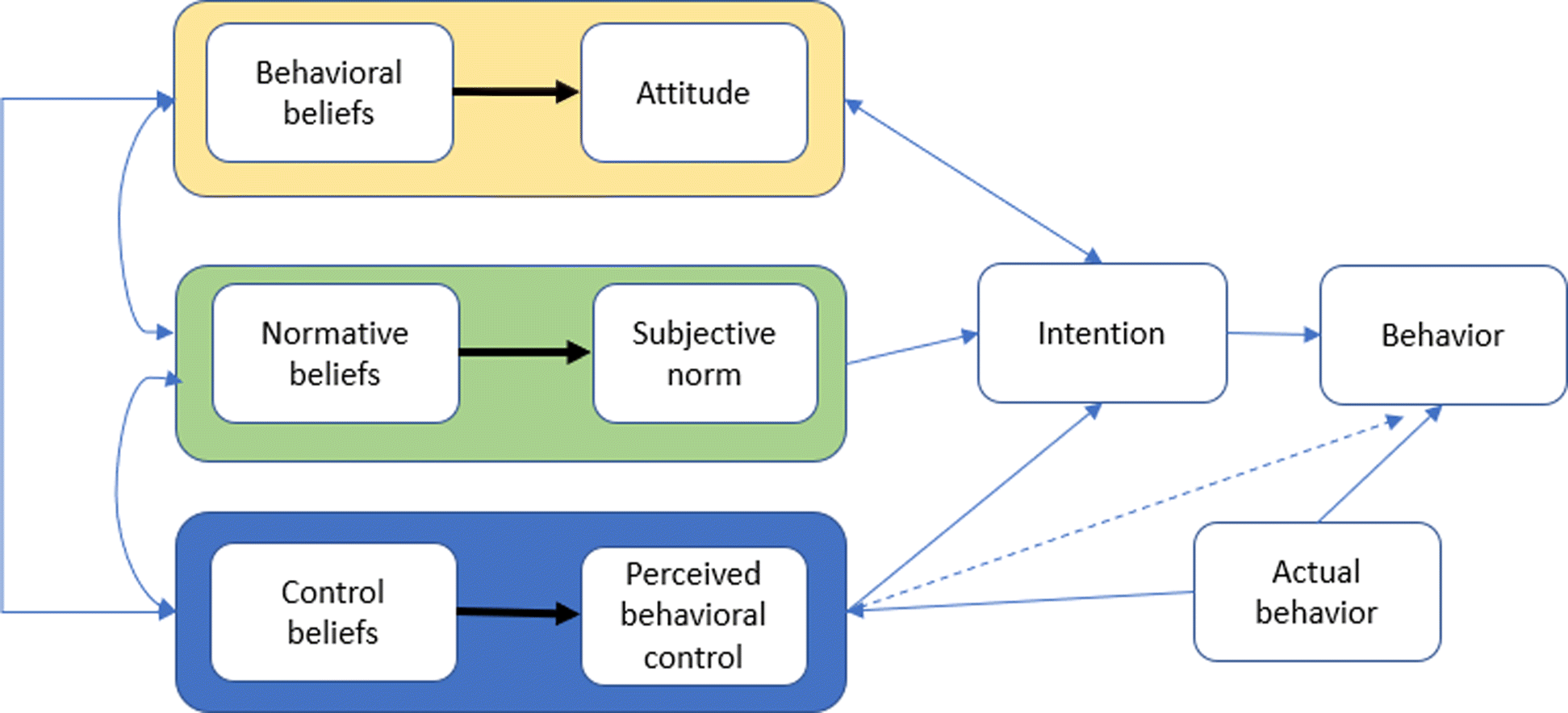

Since the majority of cyber incidents are human enabled, this shift requires expanding research to underexplored areas such as behavioral aspects of cybersecurity. This paper provides a review of relevant theories and principles, and gives insights including an interdisciplinary framework that combines behavioral cybersecurity, human factors, and modeling and simulation.

CyberBitsEtc. is a website and blog by Ganna Pogrebna (Professor of Behavioural Economics and Data Science, Fellow at the Alan Turing Institute) and Boris Taratine (Cyber Security Architect and Visionary) that focuses a lot on the human aspects of cyber security, in particular behavioural design, psychology and behavioural sciences.

The great irony is that the revolution that bitcoin set off could be the end of [financial] privacy with the launch of central bank-backed digital coins.

In a wide-ranging interview with Lauren Jackson of the New York Times, the author of “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism” talks about why people should pay attention to how big tech companies are using their information.

When customers form an emotional attachment or self-identify with a product, that sense of “mine” enhances its luster and keeps them coming back for more. As shoppers shift away from owning material things, how can marketers preserve these benefits?

The first book to call for the end of the data economy. Carissa Veliz exposes how our personal data is giving too much to big tech and governments, why that matters, and what we can do about it.

New worlds need new language. TOne of those things to name is what is happening to ourselves and our data proxies. Expanding our language from privacy to personhood enables us to have conversations that enable us to see that our data is us, our data is valuable, and our data is being collected automatically.

While some optimists think there will be a lasting positive change in our well-being model, with the quality of relationships and common goods at its centre, Manzini argues that things are not necessary going in that direction. A confrontation is required.