Richard Thaler’s Nobel Prize is a win for good design

by Erin O’Loughlin

Richard Thaler’s 2017 Nobel Economics Prize on Monday was met with more buzz around the offices of our design agency than is usual for economics news. What people outside of the industry probably don’t realize is that service designers don’t think of Richard Thaler as an economist – instead, we consider him one of our own. Thaler’s seminal theories on behavioral economics and nudging are a core part of how service designers around the globe are working to design a world that will help human beings be healthier, more sustainable, wealthier and happier.

If economics usually leaves your head spinning, don’t worry. Richard Thaler;s work on how human nature affects supposedly rational markets is not about stock markets and investments. He focuses on how humans are not the rational beings that classical economic theory assumes we are: always able to evaluate the information around us and make rational choices. Instead we’re emotional, impulsive beings, who make predictable mistakes based on heuristics, fallacies and our social interactions with others.

If that seems like a pretty important thing for classical economics to have ignored, it is. As Thaler stated on winning the Nobel prize, “the most important impact [of my research] is the recognition that economic agents are human and economic models have to incorporate that”. Thaler’s subsequent work introduces a powerful way we can incorporate this recognition into our systems – subtly guiding people towards choices and behaviors that will benefit them. He called this “nudging”, and while Thaler says that economists have been slow to embrace his work, it’s fair to say that policy makers and designers have well and truly wrapped their arms around it.

For design, the implications of Thaler’s work are clear: when we create systems, services and policies, we need to frame the available choices so that people are prompted to make the best decisions for them at a given moment of their life. This is called choice architecture, and it’s a key part of designing good services that influence people’s lives for the better and maybe, in the most favorable cases, also offer them a possibility to learn and progress in managing their aspirations. This is what we at Experientia call “service models for the evolution of people’s behaviors”..

So what are some of the practical applications of behavioral economics and nudging in design? At Experientia, we’ve used this particularly in the field of sustainability, for example, designing platforms that make it easier for people to reduce their energy consumption. These include advanced smart meters that show people where they use the most energy, or alerts that prompt people to reschedule electrical appliance use during peak energy times. Other platforms have helped to connect people to green services, like green laundry services, 0km restaurants and sustainable saunas, making it easier than ever to make sustainable choices.

In a recent project, CITYOPT, we ran a pilot program that encouraged people to reduce their energy consumption by assigning them points for every time they successfully reduced their energy use. These points were given a cash value and the participants in the study could choose a local cause to donate them to the cause that got the most points was awarded the money at the end of the pilot study. Far from the Homo Economicus model, in which we assume people would save energy because it saves them money, we instead appealed to people’s altruism and the result was that over 87% of households in the study responded to our peak energy alerts, and reduced their consumption in those times.

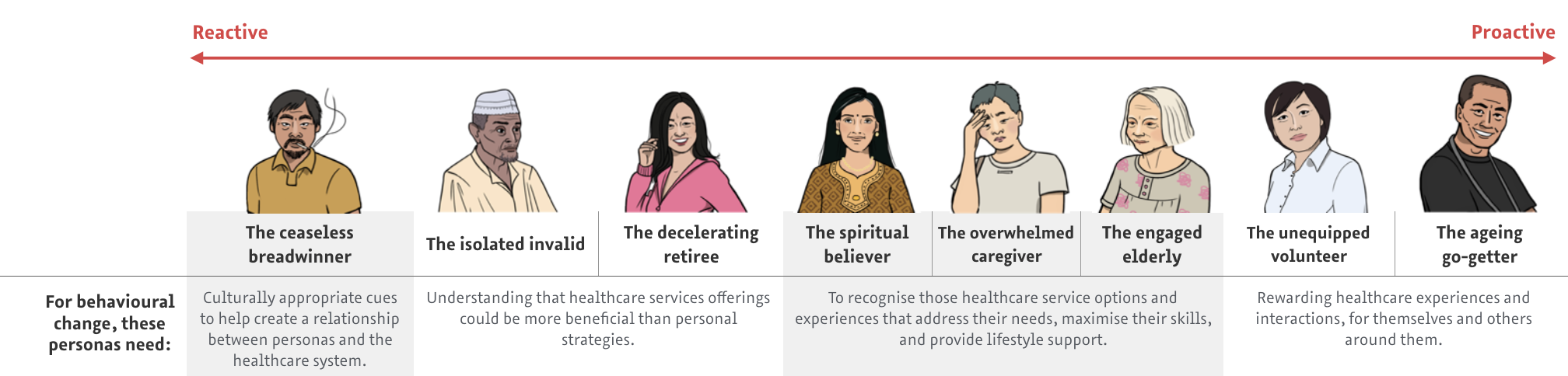

One of the ways we model people’s behaviors and choice architecture is through tools like personas. Personas can do much more than simply describe the demographic dimensions of customer segmentations. We begin the process of creating personas with in-depth ethnographic research. We base our personas on interviews, shadowing and observation of real customers, and from there we create persona archetypes that showcase people’s characteristics, attitudes and behaviors that impact how they experience a given research theme, such as a product or service. This also means our concept creation and ideation have a natural testing field – we can validate concepts quickly with the same research participants who inspired the personas.

For example, in a recent project, research with elderly people in Singapore revealed certain personas who tended to be quite isolated, and responded reactively to their health issues. Our consequent concept development was able to focus on building community-level services for this group that would combat isolation, and help to nudge their behaviors into a more proactive zone. This research not only led to concepts that were integrated into a new building development for elderly people, but was used as input into the Ministry of Health’s Action Plan for Successful Ageing.

Singapore isn;t the first government to apply behavioral economics and nudging to policy making. In 2008, Richard Thaler, together with Cass Sunstein, wrote the book Nudge: Improving Decisions on Health, Wealth and Happiness. Since then, many governments, including the US, UK and Australia, have set up units to explore how to use nudging to improve policy outcomes.

Sunstein and Thaler saw nudging as a way to influence people’s behavior in ways that could make our decision-making more beneficial to ourselves, helping to overcome the biases, automatic assumptions and habits that cause us to make poor decisions. A key part of nudging theory is that people’s freedom of choice is never removed. Nudging only makes it more likely for people to make a good decision, it never coerces people into choosing.

In policy making, this means things like making the desirable behaviors the default option, rather than something people have to opt in for. Other well-known examples include using the power of comparisons to show people that their peers are performing better – for example, to boost retirement scheme contributions, or encourage on-time tax payments. Under the right circumstances, this boosts people’s likelihood of improving their own performance. This is something Experientia has incorporated into our advanced smart meter designs, for example, allowing people to see their own energy consumption compared to people within their circles of reference: neighbors, friends, and broader community.

The applications for behavioral economics, choice architecture and nudging go well beyond these examples and they are becoming established tools in service design practices. Some have criticized nudging for being overly paternalistic (Thaler and Sunstein themselves called it Libertarian paternalism), but this misses the obvious fact that in every form, platform, touchpoint or interaction we design, we create a structured series of options for people to choose between. Thaler’s work on behavioral economics and nudging acknowledges that design impacts the choices we make and as service designers, we need to recognize this, and ensure that our designs help people to make decisions that lead to better lives.